Boy Book of the Month

No ads. No sales pitch. Just sincere, honest advice

No annoying videos will pop up in front of your reading experience as you scroll through here. Promise. (How many 'book recommendation' sites can say that?)

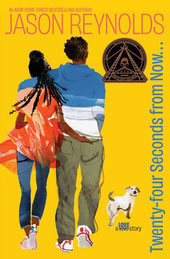

Twenty-Four Seconds from Now

By Jason Reynolds

Jason Reynolds has shown a remarkable facility for writing, thoughtfully and lovingly, to readers of a number of ages and from a range of immediate interests. He writes in the Realistic mode (When I Was the Greatest), the Romantic mode (The Boy in the Black Suit), and the superhero mode (Miles Morales: Spider-Man), among others. He writes of violence, race, and running… sometimes all at once. And he writes of all of them with a sincerity that is inclusive even when it tells the story of a very particular experience—which is something only the very best writers do. It is as though his every novel, every story is there to remind us that, as disparate as our experiences might be, we are all sons, daughters, siblings, friends, students, community members. He writes so vibrantly of the urban experience that readers feel like, whenever we open a new book of us, we are invited back to a favorite place… if we don’t already live there.

In Twenty-Four Seconds from Now, Reynolds stretches his muscles to present his most intimate portrayal of adolescence. While the outside world inevitably seeps in—and thankfully so—this story is deeply centered on the interior space of love, nerves, and the tenderness of first-time sexual vulnerability. Neon, the narrator, is alone in his girlfriend Aria’s bathroom, counting down the final seconds before they take that next step. As the seconds tick, the narrative unfolds in flashes—twenty-four minutes ago, twenty-four days ago, twenty-four weeks ago—revealing a beautifully awkward, funny, and sincere relationship. As simple as it is, it is also remarkable, this restructuring of the sex narrative from something “dirty” to something intimate.

Rather than sensationalizing sex, Reynolds renders it as something honest and emotional: grounded in affection, trust, and growth. Neon and Aria’s romance is surrounded by supportive parents, awkward moments, and real conversation. In doing so, Reynolds gives readers something rare and needed: a love story for teens that respects their intelligence, emotions, and longing for connection. Quiet, brave, and deeply felt.

Some recent books of the month

Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks

By Jason Reynolds

Jason Reynolds is a delightful storyteller who has produced a number of tonally different works. From the beginning, however (When I Was the Greatest, The Boy in the Black Suit), his work has shined when it shares the beauty and joy of relationships and community. I'm not sure anyone brings the American city to life with as much love and respect as he does.

In Look Both Ways, Reynolds creates a mosaic of ten interlinked stories that orbit the same urban neighborhood, each following a different child or group of children walking home from school. While each story stands on its own, together they create a layered portrait of a vibrant, messy, hopeful world. The brilliance lies in the way Reynolds captures the small, poignant moments—grief, love, resilience, silliness—that define the day-to-day lives of young people.

What makes this book so special is its refusal to flatten children into caricatures. Each voice feels real, and each perspective offers depth. A boy caring for his mother with cancer, kids navigating friendship and pranks, a girl dealing with the legacy of a school tragedy—Reynolds moves fluidly between tones, letting lightness and heaviness coexist. The city isn’t just a backdrop; it breathes with them.

Reynolds never talks down to his audience. He respects young readers’ intelligence, curiosity, and emotional range. The language is crisp and rhythmic, playful without being precious. The stories often veer in unexpected directions but always return to a fundamental sense of humanity.

Look Both Ways is a celebration of everyday life—the walk home from school transformed into a stage for discovery, laughter, and quiet bravery. It’s one of Reynolds’ finest books: full of empathy, full of heart, and full of kids being gloriously themselves.

CIty Under the City

By Dan Yaccarino

One of my favorite children's books in a long time! This 64-page picture book is the kind parents will read to children over and over again. Appropriate for preschool kids and elementary-school children alike, it's also the kind of book that parents will enjoy taking part in as well.

A timely volume about the value of stories and books in the lives of people of all ages, Yaccarino's imagery and text evokes in a small way Pixar's WALL-E. In the future, humans have acquiesced to the Eyes, a not-too-difficult-to-understand computer program like EM Forster's Machine (those of you who know that text). The Eyes do everything for people, and keep them from thinking too much themselves (adults will, again, be reminded of many of their own classic reading experiences, from Bradbury to Vonnegut to the Matrix). But one little girl, Bix, breaks the mold when she discovers another world, a city under the city. In the tradition of the best children's classics, adults will find multiple layers of meaning, while the text never becomes too complicated for even the youngest reader.

A brief summary of the narrative will touch on the theme, but not likely do justice to the depth of narrative and imagery, but here goes: Bix and her family live in a reasonably distant future city where human interaction (and book-reading) are passe. In their place, people stare at computer screens (sound familiar?). While the humans watch the screens, there is a screen that watches them, as well. The Orwellian Eyes monitor all things human, and they claim they are there to help (I'm sure many adults have seen Star Trek episodes evoking this theme, too).

The thing is, like most kids, Bix wants to explore her world, learn to do things for herself. She discovers the city under the city one day while running from of the Eyes. A rat (the classic motif of the lowest of the low who provides wisdom to the hero) brings her to a library, where Bix is delightfully amazed by the universe of exploration and wisdom there (my favorite scenes, both textually and visually). That's where Bix learns of past generations of humans who used to love to read, and did so without the Eyes controlling their every movement. Then she returns home to share her discovery with her parents, and the excitement only increases.

As fascinating and engaging as the story is, the highly acclaimed Yaccarino may even have created the most visually interesting illustrations of his entire career. Each page is chock full of fascinating imagery in every nook and corner of the page, and the juxtaposition of delight/joy/exploration and ominousness is masterful. Like his narrative, though, the layers of illustration do not overwhelm the young reader. Instead, they simply reward multiple readings, as only the very best texts can do. I can't recommend this book highly enough. It's the kind you not only get a copy for yourself, but copies to give to everyone you know.

Attack of the Black Rectangles

By Amy Sarig King

A.S. King is one of the greatest Young Adult authors America has ever seen, even if all of America doesn't know it yet. That being said, most of America will know about Amy Sarig King the

middle-grade writer, with her timely and focused novel, Attack of the Rectangles. King has always excelled at recognizing the general intelligence, wisdom, and, yes, maturity or

her audience, and that's exactly what she does in this exposé of the dangers of "soft" censorship in today's schools.

In this perfectly toned middle-grade novel, King exhibits once more that her characters, and her audience, are intelligent, thoughtful, and capable human beings who excel when they are treated by adults as just what they are. Of course, in this novel, it is their middle school teacher who treats the trio of main characters as thought they are fragile, vulnerable, and incapable of dealing with even the tamest of age-appropriate themes. In case you're wondering if this novel pushes the envelope too far, it doesn't. In fact, what it does do is exhibit just how dangerous the concept of protecting children from reality can be.

Get it, for yourself, or for your kids. Then have some great conversations about it...

By Ellen Hopkins

Ellen Hopkins has never shied away from the truth of some people's lives, and that's what makes here must-reading for some young (and, quite frankly, some not-so-young) people. In this one, twelve-year-old Trace has to deal with life (don't we all?) now that his older brother Will has suffered a catastophic brain injury.

In most of her earlier outings, Hopkins has dealt with protagonists who are struggling firsthand with the difficult problems life sometimes brings us. In this fluidly written, sensitive middle-grade novel, she tells the story of those family members who still have to live their lives when those around them are affected by trauma. In this case, that's Trace, your typical middle-schooler who, in many ways, Treace is forgotten as the "good son," while the family has to spend much of its time dealing with his troubled big brother.

So many children whose siblings (or parents) are suffering from trauma of one kind or another unfortunately find themselves in this situation, and Hopkins' sensitive lesson here is for them to recognize that sometimes they are also allowed to stop saying, "What about Will?" and start asking, "What about me?" A brilliant and thoughtful book.

By Andrew Smith

I was afraid of what had been happening to me.”

A. S. King has done it again! The master of writing books for young adults (and those a tad younger than young adults) continues to write books that are increasingly more difficult to explain, and yet that much more difficult to put down. Start with the minimalist cover of a house turning itself upside down, gradually, and you have a sense of... well, most A.S. King YA books, but this one in particular.

That being said, Hawking's writing, I have found, is some of the most lucid about some of the more profound questions of existence, and his The Theory of Everything is one of his finest works. Is the reader going to understand all of it? No. (I didn't.) But it doesn't make for an unworthy reading experience. Reading of any sort is supposed to light a flame of interest in readers (or stoke the fire, if it has already been lit). This book will do that. (For the record, I would also suggest this one over his more popular, but more dense, A Brief History of Time. (And for younger kids, the work he did with his daughter Lucy in books like George's Secret Key to the Universe, is also worth a look.)

Jason Reynolds writes best when he writes about characters: real people with real voices who live in real places. Look Both Ways is another of those books that gets you to fall in love with the characters that you'd swear he was writing about from his own memory.

Similar to the way he created the amazing (and, for him, sad) Long Way Down (which takes place over the course of several elevator stops from a fifteen-year-old Will's apartment down to the street, in which he is possibly going to avenge his brother's murder), this is a collection of stories told over the course of ten blocks. While Long Way Down was told in economical poetry, this is Reynolds' best voice... kids speaking extemporaneously about this, that, and the other thing over the course of their walk home from school one day.

I want to say it's powerful fiction (because it is), but that would turn people off to what it really is. What it really is is the voice of everyboy and everygirl. It's the conversations we have with best friends and frenemies, about the problems that confront each of us, large and small. It's about the interests we have, important and fleeting. It's funny and it's heartbreaking. And somehow the ten blocks worth of stories all come together in the end. Why, because Jason Reynolds is that good a writer. He writes with love, and that's what connects all these stories. Without writing down or oversimplifying, Jason loves his characters enough to make them complex and challenged, who speak the way kids speak, about the things kids speak (boogers, anyone?), and he redeems middle-grade literature with a handful of other writers who recognize children's literature doesn't mean, "Let me, an adult, preach to you about what you should think and feel, in order to be indoctrinated into society in a way that we will accept you."

Instead, like all his work, Look Both Ways, is a story for boys and girls first and foremost, done in the most legitimate voicing that makes the reader say, "Why can't all writers be like this?" Truth is, it takes a special talent, a real sensitivity, and love of one's readers, to accomplish what looks so freakin' easy! Jason Reynolds is that writer.

Don't discount the value of simple books, or graphic ones. Can you think of something that's a more simple, attractive way of getting young people to at least be introduced to some classic works of literature than providing them with three-panel drawings of them? I can't. It's a genius idea.

Will readers get the whole story of Moby Dick from the cover that you see here? No. Of course not. But there's humor in each of these cartoons, and that's enough to get any reader to at least have a foothold into the classic pieces of literature that we, rightly or wrongly, believe everyone must know. (Hint: some still have value, some don't). That being said, I was the kind of kid who would have loved Lisa Brown's book, memorized a number of pages and thought to myself, "Hmm, one day I might read the book that this cartoon is about; it looks funny/exciting/scary."

This book should be in any home where there's a hope that good stories can find a way into the minds and hearts of young readers. I can't recommend it more highly.

Blizzard: Heroism at Sea During the Great Blizzard of 1978

But is there a 13th story?

Yes, this collections was created in the interest of increasing diversity in the literary marketplace for middle grade readers, but that alone does not make it worthwhile. What makes it worthwhile is these are good stories that speak to diverse issues in diverse voices, and in doing so, they are refreshing to just about any reader. It's okay if you don't fall in love with all of these writers; no book with such diversity of themes can claim to do that. But if there is a writer or two or three you do appreciate, the world will expand for you so quickly once you see the myriad of other things that writer has written. Seek him or her out!

As I said last month, the issue with mythology collections is that they are often told by erstwhile scholars who want to "get it right" more than tell stories in the most engaging ways. Neil Gaiman, of course, knows how to tell stories in engaging ways. I, personally, have been looking for Norse myths that would engage me (a reluctant reader), and previous attempts have resulted in a stack of mostly-unread books. (My apologies if there are some good ones I simply haven't had the luck of finding--now that there isn't a legitimate bookstore chain in America--yes, that was a dig). I have recommended a graphic novel version of Norse myths (check out my site's Books for Boys page), but Gaiman's is a book for readers: people who love the sound of words echoing in their heads.

This book is for everyone who can appreciate stories, period, and I heartily recommend it as after-dinner family-time reading. (Those of you who have been following this page through the years know that I believe deeply in such things, and that such rituals become something children of all ages--yes, usually even teenagers--will look forward to). I also suggest getting your hands on the beautiful hardcover version, to exhibit the value of the thoughtfully printed word.

For example, the most basic question: why are the eastern shapes organically shaped (and small), while the western ones geometric? On the one hand, the answer is simple: the colonies, and states East of the Mississippi were formed when water transportation (and access to rivers) was necessary (and not a simple thing to bride). Therefore, rivers made for easy state boundaries. Once transportation accelerated (trains, especially), larger distances could be travelled, rivers were less vital, and states could grow in size. Of course, there's more to this, and Stein's storytelling style makes for memorable experiences.

Dan Yaccarino's I Am a Story does all of the above in his characteristic colorful style. The story begins with people gathered around a fire and proceeds through cave paintings, clay-tablet carvings, up to today's written and oral storytellings. On its own, it's a simple story, but it's an important one that parents and children share every time they open a book (like this one) together.

Let me be the first to say it: Dig should be on the short list the National Book Award for 2019, and every other book award, as well. (Honestly, I've been writing this review for months, when I would have been the first.) Dig is that good, and that important. Someone has to tell the story of racism from (various) white points of view, and A.S. King is the one person I trust with the task. In Dig, she does so with frankness, honesty, and integrity.

That being said, if that was all this genre-expanding YA novel did, it would be merely a fascinating curiosity. Instead, what King does in this as in all her novels, is quickly get the reader enmeshed in quirky but complete worlds populated by quirky but irresistible characters. Sometimes the reader falls in love with them, sometimes the reader suffers with those characters, sometimes the reader is frustrated by them, and sometimes readers even hate them. What King has always done best is create exquisite characters that are more like real people than almost the entire YA genre combined can muster. That’s why her sizable readership is so faithful to her often-challenging narratives. In short, they are not only worth the effort, but they reward the effort.

King excels at humanity in all its beauty and ugliness, sensitivity and harshness, gentleness and passion. And Dig has characters galore: 14 of them, in fact, have significant speaking roles here, and 8 or 9 of them can be called narrators. Readers will not so much need to take notes as they read as want to take notes (and hypothesize on a family tree).

Two short chapters into the novel, adolescent characters identified by their roles (The Shoveler carries a shovel, CanIHelpYou? works the Arby's drive-through, The Freak mysteriously appears anywhere throughout the globe) tell their unique stories of growing up in the shadow of white power and privilege, and the misery of being raised by parents with outdated principles. They are all damaged by attitudes passed down by their parents, grandparents, neighbors, and communities. But as King so deftly does, she imbues each of them with a spark of something that not only gives them hope but gets you pulling deeply for them.

As Dig proceeds, King weaves the various stories together and entices the reader to predict how each of these lives intersects with each other. From the outset, you understand that many of these people are related, and are almost certainly descendants of the pathologically selfish Marla and Gottfried, each of whom bears ugly personal secrets that have caused damage to their children, who have, in turn, scarred their children. A.S. King is one of the very few YA writers alive who not only acknowledges adults in her novels, but gives them voices, fleshes them out, and makes them integral parts of the lives of the teenaged characters. She alone seems to understand that adolescence is not lived in a vacuum nor is it immune to family and community.

In Dig, there are a half dozen adults who suffer from, in no particular order: inherited racist tendencies, abandonment, cancer, physical and mental abuse, poverty, kleptomania, pride, self-aggrandizement, greed, and another dose or two of racism thrown in for good measure. What’s most amazing is how King can do all this and make it all believable. Her gift to readers is an understanding of the psychology of human beings, and all her characters suffer because they are so well limbed. But virtually all of her characters also have a will to be better than they are, as most humans do. As in all her books, King reserves the most hope for her young characters: who are never irretrievably lost. Even the worst of them here (a rapist) has his moment of awakening.

In Dig, teen angst and existentialism extend themselves to the more specific issues of:

• A white girl who always must secretly meet her black best friend because her racist mother refuses to allow the latter into her home.

• Same girl who sells (and takes) drugs in order to gain the illusion of independence from a racist mother whose money she refuses to accept.

• A poor boy who has never known his father and has no friends save the white supremacist neighbor-slash-father-figure.

• Same boy who gets a job painting the house of elitist landowners (Martha and Gottfried) who look down upon him because he is a lowly working class boy.

• A poor loner who creates pretend audiences to pay attention to her whenever she rarely leaves the house, and finds her only joy in fleas and masturbation (yes, really).

• Same girl who endures an abusive (definitely physically and emotionally, possibly sexually) father.

• Another loner who travels the planet watching his father gradually dying from cancer.

• Same boy who is hyperaware of his whiteness, and can’t help falling in love with a Jamaican girl who sells bracelets on a Jamaican beach while his dying father tries to find marijuana to ease his suffering.

• Same boy who recognizes his father is too busy dying to be a father.

• Two privileged brothers who leave damage everywhere in their wake.

• And through it all, the delightful and mysterious Freak, who has special powers, can read minds, and is somehow looking out for all the others.

I’m not trying to be coy by avoiding the major plot lines here. In many ways, the story arc is subsumed in the individual characters’ struggles and the reader's desire to see the threads weave together. In any case, even if you don’t always like what you’re reading, Digis a novel to be experienced. Be sure to have a pen in hand to ask questions, take notes, and curse and cry in the margins. And be ready to sometimes enjoy, sometimes worry, and sometimes fear the revelations that occur, as you try to keep one step ahead (or behind) each of the characters. You will unravel the mysteries of their own lives along with them. Once again, King gives the reader the most honest reading experience of any YA writer I know. Dig is a brave and heartbreaking undertaking that resists any summary.

Read it. And when you're done, make sure to give it to your mother or father to read next.

Sam traces a lot of his discomfort with fitting into the world to those days, when he inextricably became The Boy in the Well. At 11, he still believes that is what everyone thinks him to be, and he still believes that the frighteningly athletic and mature-looking James Jenkins was both responsible for that event and devoted to making his life miserable in middle school.

Rushdie tells the story here of Haroun, a 12-year-old boy whose mother has left his family, primarily because her husband (Haroun's father) is a storyteller. And what good are stories when the world is in such terrible shape, right? Haroun subsequently rejects his father's stories until the world as he knows it starts to unravel.

Filled with delightful puns and fantastic animal, vegetable, and mineral characters, this is a fantasy of the highest order. When read aloud, it comes to life in a way that classic stories of this ilk always have. Very satisfying for the 10-12-year-old crowd, male and female.

The remarkable achievement is captured here in Hoose's immensely readable prose, but those who don't care much for basketball (including myself) will find the story irresistible anyway. That's the sign of a great story, compelling people, and a great writer. All three of those elements are present here. It's one of the few books each year that I can almost unequivocally say to almost everyone, "Read this book!" And when you're done, check out the many suggested items that Hoose includes at the end for further reading, as well!

What kid doesn’t see roadkill on the curbside and not want to take a closer look? Many, you say? Well, those aren’t the people this book is for.

For the rest of us, Heather L. Montgomery's—er, fresh take at splattered creatures reveals the—well, the inside story of this—um, track of the animal world. It’s an engaging, enthusiastic, storytelling-style examination that begins with a dead rattlesnake she discovered one day near her home. Unable to resist the snake's, um, charm, she digs right in and dissects it (noting, properly, that she made a few bad decisions in touching, let alone examining, the still-poisonous creature). From there, she reveals how her own curiosity led her to discover more about roadkill, and she takes us on the ride with her.

Montgomery is a wildlife researcher who shares her enthusiasm at every turn afterward through the southern half of America. Then she takes her show in the—well, on the road across the globe, inquiring of scientists and roadkill fans of their expertise. In Australia, there are biologists searching for the cure to cancer by examining Tasmanian devil carcasses; elsewhere, a scientist who discovered a previously unknown bird species by examining a solitary wing; and even a restaurant that serves up a tasty corpse du jour.

Throughout, Montgomery is unafraid to share that science can be gross, and that researchers need to get their hands, um, dirty, to come to any real discoveries. In that, this is a refreshingly honest narrative.

I suppose another iteration of this book would have more charts, graphs and—well, maybe pictures, and that would really make this irresistible, but the writing is so good that it's hard to not want to finish each and every chapter.

November Boy Book of the Month

Nevertheless, We Persisted: 48 Voices of Defiance, Strength and Courage

By Multiple Authors

The title says it all. If you’re at all interested, get the book and read the stories that interest you most. Then try to resist reading the rest of them. My personal favorite (*right now. I reserve the right to fall in love with others as I reread them): “They didn’t succeed—I Survived” a story by ninety-six-year--old holocaust survivor Fanny Starr. Where others are not quite as strong, there are those, like this one, that make you understand immediately what persistence really means. It gives perspective to those who do not yet understand the word.

October Boy Book of the Month

Rabbit & Robot

by Andrew Smith

It may be Andrew Smith's wildest and craziest book yet, but don't let that scare you. It's also more accessible than some of his latest work, which was wild and crazy but also dense.

The novel takes place on board the Tennessee, a spaceship orbiting a war-torn, ruined earth. Addict Cager Messer has been transported here by best friends Billy and Rowan to get

him clean, but the weirdness on board here is as bizarre as any drug trip he'll ever have.

In no particular order, Cager confronts: world destruction; haywire Douglas-Adams-esque spaceships; hyperemotional cannibalistic robots; quirky blue shapeshifting aliens; a bisexual French

giraffe (my favorite); pessimistic tigers and self-centered apes with Boston accents; horny robotic personal assistants; enough gender fluidity and artificially intelligent life

forms to keep one's head delightfully spinning; and the possibility that he, Billy and Rowan are the last humans in existence (well, until computer programmer Meg Hatfield and her best

friend come aboard).

This is the kind of book you will want to read if you feel like laughing out loud and reading passages out loud in outrageous accents to your friends, who will then also laugh out loud. And when your teachers show concern that you're having too much fun reading, you'll discuss the ending with them, to show that humor and mayhem are the best ways to confront some of the biggest questions of existence: in this case, what does it mean to be human?

The cover, by the way, tells you a lot about what's inside--a creative conglomeration of stuff all over the place! Only Andrew Smith could write this book and keep it together.

September Boy Book of the Month

Long Way Down

by Jason Reynolds

I have read and held onto this book for a while now. See, the thing is: it's not for everybody. It's not

for someone who hasn't experienced loss, who has never felt anger, who has never been driven by the need for revenge, or who doesn't care to think about consequences. (Is there anybody

left?)

Long Way Down is a powerful short novel in verse (don't worry, the poetry is not intrusive). When it opens, teenage Will's brother Shawn has been shot and killed. As it turns out, Shawn's death is the latest in a long string of violence that started years and years ago. But Shawn is determined to get revenge. He gets Shawn's gun, leaves his apartment, and takes the elevator downstairs to enact the rules of the street: no crying, no snitching, get payback. What Will is not prepared for during the long trip down is a series of supernatural visits from victims of violence that have affected his life without him knowing any of it. Now, however, he is going to know the truth. Once armed with the truth, will he remain a pawn in an endless game of chess that has no winners, or will he break the pattern and claim life?

Long Way Down is certainly Reynolds' most haunting book yet, but still retains the mastery

and beauty of storytelling.